Off the Walls

Michael Amsler

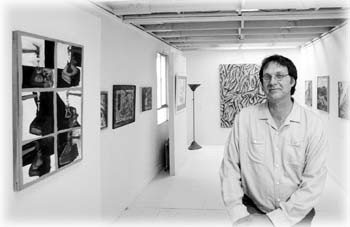

Painter William De Raymond in the gallery space of the Studio.

In a world of commercialism, alternative galleries challenge the norm

By Gretchen Giles

WALK INTO an art gallery, I dare you. When the beautiful black-suited androgyne coolly looks up at you from the Details or Art News magazines spread open on the retail gallery’s front desk, the shamefully low numbers in your bank account seem suddenly to be emblazoned across your chest. These small digits are counted up in one short glance before the androgyne’s eyes flick back to the magazine’s slick pages. But be certain, one eye is always trained on your skulking back as you attempt to walk noiselessly around the room, becoming short of breath in the rarefied oxygen contained by those sterile white walls. Slightly dizzy, you encounter work that makes almost no sense at all, but because it’s been canonized in the gallery, you know that it must be good.

When, stifled and reeling, you finally feel for the door, the watchful eye from the desk contains a baleful certainty that you’ve exited with a piece of art under your coat. Once outside, you check your pockets just to make sure that you actually didn’t steal anything.

Where in this scene is contained joy, insight, recognition, redemption, true sorrow, or even beauty? It might be in the gallery, but if you can’t get it into your eyes, mind, and heart–it don’t mean a thing.

But art galleries are changing. The high-stakes gambles of the unstable ’80s art world are finally fading, and many artists, both in Sonoma County and abroad, are looking to subvert a system that they feel is artificial, unfair, and sometimes damaging to their work.

Contrast the above, for example, with sitting on a sofa at Charles and Georgia Churchill’s Santa Rosa Redwing Blackbird Gallery. The Modern Jazz Quartet wafts from the speakers, Georgia’s been crushing watermelon for summer drinks, and Charlie’s assemblage sculpture–wrought from the slickly painted curves of new motorcycle parts and neon–winks in the clear afternoon light streaming in from the windows of the couple’s home-based gallery space.

Stand in a shaft of pure sun in the former living room of Cloverdale sculptor Carol Setterlund’s home, an elegantly empty room that is permanently peopled only with Setterlund’s rakish, anguished, and joyful busts and torsos. Feel free to lightly stroke what you see.

Walk through the warren of reclaimed old Navy buildings restored into workspaces named the Studio in Santa Rosa. Step from the green gloom of the old military-styled hallways into a narrow, white-clean cathedral of a gallery in which the Studio collective shows its art. Ask what a particular painted image means and get an answer.

Maybe best of all, sit on the dusty floor of Susan “Sam” Wolcott’s Painter’s Eye gallery in Petaluma while the pale yellow wings of a rafter-bound butterfly float down as the insect is disemboweled by another. An enormous, reclaimed building, the Painter’s Eye houses Wolcott’s own studio space in one half, and the gallery in the other, a seamless interplay that is enlivened by Wolcott’s own large, expert canvases and her collections of old foam buoys, desiccated road kill, and camouflage netting.

Narrowly miss sending a delicate ceramic from its pedestal to the floor because you’re actually having fun.

Michael Amsler

Seeing Double: Assemblage artist Charles Churchill reflects before his work.

FROM THE HOME-BASED to the collective to the workspace, all of these are vital art galleries–and there isn’t a Details magazine among them. “Alternative galleries are a place to see everything else,” says California Museum of Art director Gay Shelton, seated on a stool at a deli near the museum, picking at her lunch. “Everything that no one’s had a time to make a market for yet.

“Do I see them growing in this county?” she asks rhetorically. “Yeah. I think I could say that, because we don’t have a real strong gallery infrastructure here. We don’t have a lot of retail galleries. We have the museum, we have the Sebastopol Center [for the Arts], we have the venues that the Cultural Art Council offers, but for a number of artists, the exhibition opportunities are few and far between.”

For Shelton, a painter herself, the central question for an underrepresented artist is “How can I show my work to my audience?”

From restaurant walls to the well-regarded shows hosted by Santa Rosa’s Elle Lui hair salon to the popular ARTrails open-studios event hosted by the Cultural Arts Council for a few weekends each fall, to the similar Art at the Source event sponsored each spring by the Sebastopol Center for the Arts, to the insightful exhibits mounted by director Michael Schwager at Sonoma State’s University Art Gallery, to the opening of their own homes and studios, artists with little or no affiliation with traditional retail galleries are finding ways to exhibit their art, an act that Shelton sees as paramount.

“I’m talking about the need for an artist to share his or her work,” she explains. “There’s a psychological need that completes the creative circuit. You make a piece, you labor over it, you work to discover your own potential at making art, and somewhere along the line you need to have intercourse with the world, you need to have that work go out to the public and to feel the ways in which it’s appreciated or not appreciated, and that can inform the work in the future.”

But then there’s that niggling little cash-flow problem. Materials, canvases, food, rent, and cat kibble all cost money. And while the notion of the starving artist has a certain romantic appeal, the reality of a hard-working artist’s poverty is far less glamorous.

Shelton, who has waited tables to support her painting, and who works late nights in her studio after long days at the museum, remains a purist. “I’ve seen a lot of local artists start out with work that had a lot of vitality, and then it’s been channeled by the market–and I’m talking about the tourist trade–and so now they’re making some very predictable, kind of little tchotchke things,” she says. “Yes, those artists are making a living from their art, but is there any art left in their art?

“They have made a choice, and I’m not begrudging them that choice; I’m just not interested, I’m not part of their audience anymore. Because I want to make art that has some depth, I’m always trying to hold my art a little bit away from the market.

“Now,” she says, warming to her subject, “that’s the advantage of a retail gallery: If you can find a retail gallery that’s got vision, they can allow you to make the work you’re going to make already, and promote it and find an audience and find a collector base for the work.”

Citing the Susan Cummins Gallery in Mill Valley as one that helps to nurture such artists as painter Jim Barsness, whose challenging canvases were recently exhibited at the California Museum of Art, Shelton nevertheless maintains the hard line. “Always, commodifying your work takes something out of it,” she says emphatically. “And we’re getting down here to what I would think would be the most important aspect of a successful alternative space: It would have nothing to do with commodifying the work. It’s presenting the work, it’s creating an audience for the work. Nothing needs to be sold, you’re not asked to create little trinkets to sell to tourists.

“In that respect,” she says, setting down her fork, “I would say that the Painter’s Eye is maybe more successful than, say, ARTrails. At the Painter’s Eye, there will be pieces on the wall for sale, but it’s a very casual process. The process that goes on there is typically more pure.”

IF ART IS JUST HOUSED in those galleries that are not comfortable to go in, or if it is just housed in museums, there is no possibility of it being spread around and no consciousness that this is really important to our social fabric and to our culture,” says ceramicist Anne Peet, seated cross-legged in shorts on the floor of the Painter’s Eye.

Peet and husband Roger Carrington are among the artists who rent the Painter’s Eye to exhibit their work. Establishing the gallery four years ago, Sam Wolcott charges just enough to offset her rent, allowing for a reception and a two-weekend exhibit. Not a vanity gallery–where artists of any level may exhibit if their pocketbook allows–the Painter’s Eye screens the work, striving to maintain a level that Wolcott characterizes as being higher than that of “watercolors of kittens seated in sunny windowsills.”

“It’s a horrible world, the regular gallery scene,” says Peet.

Wolcott nods. “It’s so against the artist’s spirit,” she says, noting that traditional retail galleries need artists to survive, a concept that most struggling artists neglect to consider. “The whole gallery atmosphere is built upon intimidation of the artist,” she emphasizes, adding that in a perfect world, artists would shop galleries for those that could best provide for them, not the other way around.

Often, Peet notes, “galleries just want the last work you did. Well, suppose you’re done with that, OK?” she shrugs. “You can’t keep doing the same thing again and again. If you have more control, you can change your work as you need to. You don’t get stuck having to make the work you don’t want to make.”

Wolcott agrees. “I’ve felt that pressure. I mean, look at many of the gallery artists: Their work hasn’t changed in 10 years, and you know that if they’re good artists, their work is changing somewhere else inside. That’s what I meant by saying that the galleries almost seem to work in opposition to the artist’s spirit. Because the spirit is to move and change, and you’re lucky to find a gallery that can do that or that has collectors that will do that.

“I’m sure that galleries have their place and have had,” Wolcott says thoughtfully. “Things are just moving so differently now. There are just so many other venues for exposure that artists can take on a little more of that.”

THE REN BROWN COLLECTION in Bodega Bay specializes in contemporary Japanese printmaking, as well as hanging about 40 percent of its gallery space with such local artists as Micah Schwaberow. Brown is supportive both of local artists and of their attempts to self-market their work.

“I keep telling the artists that come by, the more exposure the better, in any and all kinds of venues,” he says. “My aim is also to challenge the viewers, and not just put up pretty pictures that would go well with the fabric of the sofa.

“But,” he continues, “I worry about some alternative spaces like restaurants, because I think that the artists get used–in terms of the sale of the artwork. I’ve been approached by a number of businesses [that wish to borrow some of the work he represents], and it’s readily apparent to me that they’re not interested in the artists, they just want some pictures on the wall other than those posters that they can afford.”

Overhead is of little importance at the Redwing Blackbird gallery, where assemblagist Charles Churchill mounts an annual show in a gallery space he built for his art and his wife Georgia’s storytelling and acting performances. The gallery is never idle; when no outsiders are invited, it doubles as the Churchill’s bedroom. While Churchill has enjoyed success in retail outlets, he has felt the need to have an exhibition space as personal as his work itself.

Nor does overhead affect Carol Setterlund, a sculptor regularly affiliated with retail galleries, but who is just beginning to open her home to other artists for exhibitions.

In the cluster of workspaces at the Studio in Santa Rosa, artists have come together over a need to share their vision. With the landlord’s donation of two upstairs rooms, Studio artists knocked down some walls, set in some skylights, painted the walls, and created a stunning long room in which to exhibit their work. Ceramicist Glenneth Lambert and painter William De Raymond are among the 10 or so artists involved in this project, which includes monthly potluck receptions with artist talks and slide shows of new work.

“It’s kind of a funky old space,” Lambert admits, seated on a couch in De Raymond’s painting-adorned studio. “But you know, people are intimidated by galleries, so maybe this helps to break that down.”

The Studio is definitely a low-profile operation (finding it is half the fun), but De Raymond hopes to see its role expand. “I don’t see this as an alternative space specifically,” he says. “We’re doing the best that we can with what we have available to us. Ultimately we’d like to create an art center in Sonoma County just like any other art center.”

Like most artists, Lambert and De Raymond envision a day when their art alone will provide for them. “I haven’t had a lot of success with showing galleries my work and having them want it,” says De Raymond. “I’m not going to say that it’s not good enough to be shown anywhere. I’m good at what I do and I do what I do, and yet I’m not at the point yet where I’m able to live off my artwork.

“And then again, you have a whole system where it seems to be designed so that a few people will make a lot of money and not very many will make enough to live on.”

But isn’t that just the common unfairness of life? Don’t many people play college ball, only to watch as just a few are picked for the big leagues?

“We know that Michael Jordan belongs in the Bulls,” laughs De Raymond, who is well over 6 feet tall and is seated on his couch with a basketball by his feet. “But if I think that I’m the Michael Jordan of the art world, why aren’t I being shown in the galleries? If I know that I can jump from the foul line and dunk it behind my head as an artist, and yet nobody else can see that that’s what I’m doing, what’s going on?

“You can find work being done here that is on par with work being done in some of the finest places in the world,” he continues. “I’ve seen enough artwork, I’ve been to enough museums, I’ve been to enough galleries, to say that. We just happen to be here. Nobody’s been clamoring to do anything about it. All I know is that there are some serious artists working here, and here we are. This is it.”

Back at the Painter’s Eye, Anne Peet stretches her legs out on the floor. “What I like about art,” she smiles, “is that it’s a life thing, not just a commercial proposition. I mean, there can’t be an understanding of that unless people can acquire art and share it. And that is where this,” she says, waving her hand around the room, “is very, very important. It’s crucial.”

Always ready with ideas, Sam Wolcott encourages artists to rent unused storefronts to hang short simple shows. Above all, getting the work out there is paramount.

“Because the last thing you want to do,” she says with a chuckle, “is to end up in an ivory . . . basement.”

From the July 2-9, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.