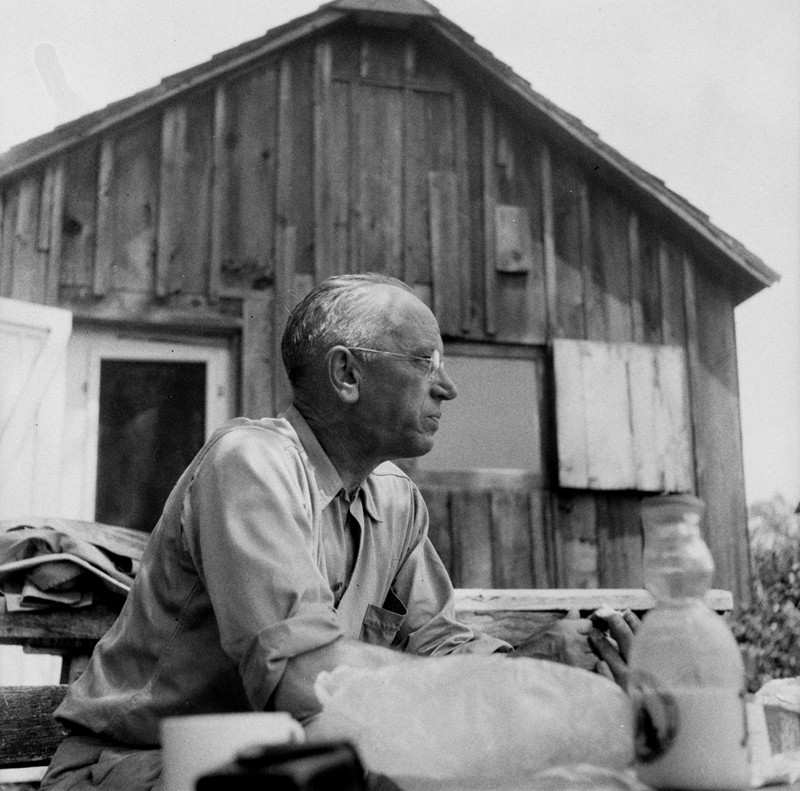

A brave yet bashful author, Aldo Leopold never cared for fame and fortune. Though his classic 1949 collection of essays, A Sand County Almanac, has sold millions, he himself remains largely unknown today. “Aldo who?” a quiz show contestant might well ask.

But for decades, family members, friends and followers have kept his flame burning brightly. Now, scientists, teachers and activists want to make the visionary environmentalist, who died in 1948 at the age of 61, as well-known as his book, and as respected a figure as Henry David Thoreau, author of Walden; John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club; and Rachel Carson, whose feisty polemic Silent Spring helped create the Environmental Protection Agency.

Unlike Thoreau and Muir, Leopold was a dedicated family man, college professor and government employee. Unlike Carson, who achieved sudden fame, he never received national acclaim in his lifetime, not even from conservationists. Still, over the past decades, his work has gained respect. His stunning essay “Thinking Like a Mountain” has inspired half a dozen or so imitations with titles such as “Thinking Like a Watershed” and “Thinking Like a River.”

Pretty soon, ecologists everywhere may be “Thinking Like Leopold,” if they aren’t already, which means thinking ethically about the earth.

The year 2013 might be the Leopold moment for our time, and just in “the nick of time,” to borrow Thoreau’s phrase, now that climate change has undeniably arrived. A snazzy documentary about Leopold titled Green Fire, completed two years ago, is now reaching large audiences—in April, it airs nationwide on PBS—and the prestigious Library of America has just published a collection of Leopold’s best works edited by Curt Meine. Meine headlines the three-day Geography of Hope Conference, running March 15–17 in Point Reyes Station, that’s all about the author of A Sand County Almanac.

There’s no more fit setting for the conference than West Marin with its rich agricultural history, brave new organic farmers and ferocious battles about trees, water and, most recently, the oyster, the lowly mollusk that made Point Reyes legendary and that continues to divide friends and families ever since the federal government ordered the closure of Drakes Bay Oyster Company. The wounds haven’t healed yet. Robert Hass, a former U.S. poet laureate and a longtime resident of Marin, hopes that the conference will create a calm atmosphere to talk about the oyster wars. “Oysters and the environment are an inescapable topic,” he told me the day after he returned from a trip to Myanmar. “This year’s conference is more relevant to Marin than any other we’ve ever had.”

Co-sponsored by the U.S. Forest Service, the Aldo Leopold Foundation and the Center for Humans and Nature, this year’s get-together—the fourth in five years—brings together scholars, activists and poets from near and far. Geography of Hope fans and followers can hear lectures, watch the film Green Fire and meet its producers, go on outings to farms and fields, watch birds, learn about habitat restoration and taste organic goat cheese at Toluma Farms in Tomales. The documentary Rebels with a Cause will also be shown. Never before have so many outstanding ecologists and conservationists come together to talk about Leopold’s identities, ideas and ethics that, Leopoldians insist, can help save the earth if farmers, hunters, ranchers and tourists work together.

The rallying cry for the 2013 conference, “Igniting the Green Fire: Finding Hope in Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic,” grew organically from previous gatherings about farming and water. The very first conference, in 2009, focused on the “geography of hope,” a phrase coined by Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Wallace Stegner, who died in 1993. These days, Stegner serves as a friendly environmental ghost who haunts West Marin and its park rangers, tree huggers and citizens who want to wander wild lands before—as Joni Mitchell lamented in her pop anthem “Big Yellow Taxi”—they’re “paved” over with parking lots.

In the crowded field of Aldo Leopold studies, nobody knows more about him than his official biographer, Curt Meine. A modest Midwesterner like Leopold, Meine gives credit to all the players on the Leopold team and insists that the ecologist’s legacy ought to be written and rewritten by everyone in a community, whether it’s Point Reyes or his own in the Driftless area of Wisconsin, a Midwestern version of Northern California. Like Leopold and Stegner, Meine expresses hope about the environment, though he doesn’t lapse into glib optimism. “Every landscape is pregnant with hope and despair,” he tells me the day we talk, which happens to be the anniversary of Leopold’s birth. He adds, “No landscape is so bleak that it’s hopeless. Even in the most despairing environments, something positive can be done.”

Almost everyone who writes about Leopold has an epiphany. Meine’s took place in 1982 in the University of Wisconsin library. An eager graduate student, he opened a box with Leopold’s papers and held them in his hands as though they were the Dead Sea Scrolls. “That particular box contained the papers that were in his desk when he died,” Meine tells me. “Some were typed, some handwritten, some the barest of fragments.”

Three decades later, he looks back at the evolution of his career from fledging student to venerable scholar. He also sees, perhaps clearer than ever before, the growth of Leopold’s thinking about the wilderness, that quintessential American landscape. “As a young man, the wilderness was his hunting ground,” Meine says. “Later, he prized it as a historical site, because so much of the American past was enacted there.

“In the 1930s, with the Dust Bowl, he developed an ecological sense of the wild. In the 1940s, he recognized its importance as a living laboratory for scientists, and, near the end of his life, it became a spiritual place. On his deathbed, he was a staunch advocate for wild lands and at the same time a defender of farms and farming.”

[page]

The film Green Fire shows Leopold wearing all his many colorful hats. There’s a stunning image of him, for example, in 1909 in the Arizona territory. A recent graduate of the Yale School of Forestry, he recreated himself as a cowboy with a six-gun and a Stetson, employed by the fledgling National Forest Service. Leopold’s friend, Rube Pritchard, boasted in a letter to his mother that he’d rather work in an American forest than be crowned king of England. Leopold added modestly, “I’m beginning to agree.”

Co-produced by Ann and Steve Dunsky, both of whom work in Vallejo for the U.S. Forest Service, Green Fire offers Leopold’s own words as read by Marin County’s inimitable Peter Coyote, whose deep, resonant voice is instantly recognizable. “I never prepared to read from Leopold,” Coyote tells me. “I’ve done voiceovers for hundreds of films, and I always work like an improvisational jazz saxophonist.” Still, Coyote couldn’t have been better prepared. A longtime, heartfelt fan of Leopold’s work, he grew up on a farm, and later learned about nature and spirituality from California Indians, Zen Buddhists and from his buddy, Gary Snyder, who taught him that “the wild has his own dictates.”

“Coyote is amazing,” Ann Dunsky tells me. “He read perfectly from A Sand County Almanac on the first take.” She and her husband come to Leopold’s work from opposite directions. He’s an Easterner; she’s a Westerner. He grew up thinking hunters were evil; she came from a family of hunters. He’s a dogged researcher; she’s a creative filmmaker. These days, they share a love of Leopold, whom they see as a lifelong moderate who avoided extremes and whose work can bridge clashing communities and opposing schools of thought.

“When I first read A Sand County Almanac as a teenager,” Steve Dunsky tells me, “I saw it as the ruminations of an old man with quaint stories. I went back to it in my 40s and found it a complex work that examines the big picture and sees human beings as a part of the natural world. His ‘land ethic’ links all of us and every species on the earth.”

Professor Kathleen Moore, a philosopher and ethicist at Oregon State, believes that everyone who graduates from college ought to have read Sand County Almanac and understood it. “If students are too busy to read it,” she tells me, “they ought to see Green Fire.” When undergraduates and colleagues want to know her favorite passage in Leopold’s classic, she turns instantly to the section titled “The Outlook” and reads: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

A fiery teacher, impassioned moralist and compassionate writer, Moore doesn’t think the sky is falling, but she insists that the oceans are rising fast and furious, and argues that if humans don’t act wisely, quickly, “we’ll soon be caught between hell and high water.” Leopold’s ethical values can help, she says, “if humans stop thinking of themselves as solitary beings and recognize they’re part of a system and have an impact on it.”

Like Meine and Stegner, she’s hopeful and whimsical, too. “The beavers are back in the woods of Oregon,” she tells me. “They’re resurgent, though I can’t speak for the beavers on the football team.”

Wendell Gilgert calls himself a Leopoldian, and though he’s not a professor, writer or filmmaker, he does have a BA and an MA from Chico State. In high school in 1964, his English teacher told him to go to the library, find a book and read it. A Sand County Almanac changed his life. For decades, he worked with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. In 2011, he became the working landscapes program director at Point Reyes Bird Observatory Conservation Science, a Marin County nonprofit. These days, he goes into fields and farms, talks the farmer talk and walks the rancher walk.

“I don’t tell anyone what to do or how to improve what they’re already doing,” he explains. “I suggest tools they might use. I learned that from Leopold.” Gilgert hopes farmers and ranchers will be effective stewards of the land, protect watersheds, enhance soils and guard wildlife habitat. Mike and Sally Gale in Chileno Valley, and Loren Poncia in Tomales, operate sustainable ranches that might be emulated, Gilgert says.

The most surprising take on Leopold comes, not surprisingly, from Robert Hass, a guiding light of the Geography of Hope Conference who put Marin’s geography on the literary map of America in volumes of poetry such as The Apple Trees at Olema. During the course of our early morning conversation, Hass compared Leopold to T. S. Eliot, another Midwesterner, born a year after Leopold, whose quintessential modernist poem The Waste Land offers a geography of despair in lines such as “Here is no water but only rock.” On first glance, Leopold and Eliot seem like polar opposites, but Hass argues that A Sand County Almanac, like The Waste Land, is a modernist work in that it’s made up of “patches and fragments.”

Furthermore, he believes that The Waste Land is an ecological poem and that, despite Eliot’s sense of alienation and despair, was written “out of a hunger for wholeness.”

If anyone at the Geography of Hope Conference can fuse seeming opposites and bring together apparent foes, it’s surely Hass. No one followed Marin’s oyster wars as sensitively as he, and no one hungers more for the wholeness of the community than he. Hopeful and fearless, he’s prepared to talk about the links between Wallace Stegner and Aldo Leopold, and eager, too, to persuade the volatile members of Marin’s divided community to sit down with one another and share ideas.

“I hope that there’s time for poetry, too,” Hass says, instantly conjuring an image of a hawk from the work of Robinson Jeffers. “We’ve got to have poetry to have a geography of hope.”