F/T Job Wanted

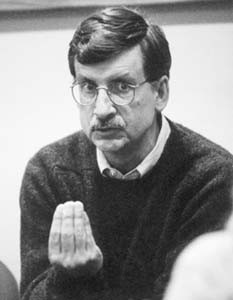

Making a fine point: SRJC history instructor and Academic Senate member Marty Bennett gathers support to back a bill hiring more full-time faculty.

Michael Amsler

SRJC instructors join statewide call for more full-time teaching positions

By Paula Harris

IT’S 5:30 A.M. as part-time Santa Rosa Junior College history instructor Alix Alixopulos edges his old Ford van (actually a traveling makeshift office–crammed with text books–that has logged more than 200,000 miles) onto freeway commuter traffic.

The longtime Sonoma County adjunct instructor and Santa Rosa resident spends tedious hours on Highway 101 shuttling between college campuses. He teaches morning classes in Pleasant Hill, beyond Vallejo, then drives back to Santa Rosa to teach afternoon and evening courses at SRJC.

Alixopulos, 57, a “freeway flyer” (the term used for traveling adjunct faculty) for about 13 years, calls his situation a form of migrant labor. He hates the instability and the commuting but tolerates the exhausting lifestyle because of his love for the work. Alixopulos longs for a full-time position, but, in his own words, “it’s never going to happen” because of the disparity between full- and part-time faculty positions at community colleges.

“[Administrators] would rather hire part-timers, or someone at the lower end of the pay scale,” says Alixopulos, who has 30 years’ teaching experience. “People like me get kind of trapped, but I teach because I love it.”

According to the California Federation of Teachers, two out of three faculty members in community colleges statewide are part-time employees. In the fall of 1997, the part-time instructors in California’s community colleges composed 43 percent of staff positions, a far cry from the 25 percent mandated by law 10 years ago. A December 1997 report by the state chancellor’s office found that only four of California’s 71 community college districts have achieved that goal–SRJC is in a three-way tie for the 16th ranking in the state for the highest percentage of hours of credit instruction taught by full-time faculty.

Typically, in a trend that’s being increasingly felt nationwide, employers are hiring part-timers as a cost-cutting measure. These faculty members are poorly paid, receive no benefits, and have little in the way of support.

“A part-timer is paid 62 percent of what a full-timer is paid in hourly assignments,” says Marty Bennett, an SRJC history instructor and a member of both the CFT and the American Association of University Professors. SRJC has 305 full-time faculty and 755 part-time instructors, he says.

In addition, tenured faculty are not being replaced when they depart or retire, leaving few instructors on the time-honored tenure track. Critics say the total effect undermines the teaching profession and erodes the overall quality of higher education.

However, there are some attempts to reverse this budget-driven trend. Last week, the SRJC Academic Senate, which represents the faculty, unanimously passed a resolution recommending that the college commit an annual portion of its budget to increasing the ratio of full-time to part-time faculty by at least 20 percent over the next five years.

The Academic Senate also voted to create a resolution on giving pro-rata pay to adjunct faculty.

Bennett says some SRJC departments, such as computer information sciences, English, and English as a second language, are seriously hurt by the imbalance. “We envision having a task force to look at needs of particular departments on campus,” says Bennett.

The move by SRJC is tied to the statewide effort to boost staffing levels. A number of legislative bills seek to create 2,000 new full-time faculty community college positions annually for five years. Other bills would create a permanent budget category to fund full-time jobs and would require part-time faculty to be compensated at a salary of a full-time faculty member with comparable training and experience.

ON MONDAY, a rally in Sacramento sponsored by the CFT and co-sponsored by the state Academic Senate, the California Teachers Association, and the Faculty Association for California Community Colleges underscored the situation.

“There’s a great need for change,” says rally organizer Tom Tyner, president of the Community College Council of the CFT, during a telephone interview from his Fresno office.

“Part-time staff are at a great disadvantage, and the majority are not choosing to work part-time, but they have no option. It’s the only avenue into community college teaching right now.”

Critics say the overreliance on temporary part-time faculty is detrimental to students. Through no fault of their own, part-time faculty are not as accessible on campus, are less available for mentoring, and have little say in the decision-making at the college. “Now most of my energies are spent commuting,” says Alixopulos, adding that there’s little time left to plan classes.

“You’re reduced to what you can do without too much preparation.”

Tyner says such hiring practices send a negative message to students. “They see the hypocrisy and irony of our educating and training them for gainful full-time employment while using primarily part-time employees. It’s exploitation,” concludes Tyner, who likens the situation to the United Parcel Service’s strike last August when part-time UPS workers made a compelling case that garnered widespread public support.

“We’re hopeful that the legislative route will be successful. If not, there are other alternatives for us to pursue like the UPS workers did,” says Tyner, adding that a strike is definitely a possibility. “When you have over 30,000 part-time faculty throughout the state, you have the numbers to shut the entire system down if the situation gets desperate enough,” he warns.

He says the money is available to create the jobs through legislation, but that the public needs to be made aware of the situation. “Any support we can get at the local level filters up to the state level,” he says.

“Ultimately it will depend upon public concern and financing from state and local levels.”

Meantime, Alixopulos and thousands of other freeway flyers continue to take to the roads to pursue their dream of academia. “Most part-timers would give anything to be able to work full-time,” he says. “Teaching isn’t a hobby for us.”

From the May 7-13, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.