Harvest of Fear

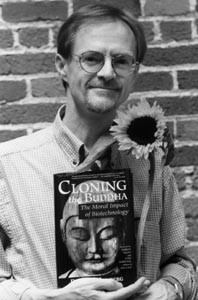

Seeds of doubt: Author Richard Heinberg thinks genetically engineered crops may yield a grim harvest.

Author Richard Heinberg takes a skeptical look at genetic engineering

By Patrick Sullivan

UNDER COVER of darkness, a small group of people enters the quiet cornfield and goes to work among the rows, using their hands and feet to pull up crops and stomp them flat. When the intruders finish their task and depart, they have ensured that the harvest isn’t going to match the expectations of the farmer–who is, as it happens, a plant biologist at the University of California at Berkeley.

The crop stompers also have fired the first shot in what may be a newly confrontational battle against genetic engineering in the United States.

For this is no ordinary cornfield. Before the crops were destroyed, the Berkeley location was the site of a university experiment in genetically altered corn, part of an attempt to learn which genes are responsible for corn’s nutritional traits so that researchers can eventually produce sweeter or more protein-rich plants.

The crop-stomping incident, which took place earlier this month, underscores the strong reactions provoked by genetic engineering, the controversial high-tech practice of manipulating DNA to, among other things, create new varieties of plants and animals. While supporters call it the best hope to end world hunger, opponents say genetic engineering poses an ominous threat to human health and the environment.

The group of crop-pulling protesters–which reportedly included activists from Sonoma County–was inspired by environmentalists in Europe, who have long employed such tactics to dramatize their opposition to what they call “Frankenfoods.” According to some observers, the Berkeley crop pull and two other recent actions targeting genetically modified commercial cornfields in the Central Valley may be the first time these tactics have been employed in the United States.

And it won’t be the last, according to Richard Heinberg. The 48-year-old Santa Rosa author, whose latest book, Cloning the Buddha: The Moral Impact of Biotechnology, a radical critique of genetic engineering due out in late August, was not involved in the Berkeley action. But Heinberg–who will read from his book on Aug. 26 at New College of California in Santa Rosa–supports such tactics because he fears that Americans are rapidly turning their farms and supermarkets over to genetically modified foods before anyone determines what dangers those products may pose.

While Heinberg’s book paints a grim picture of the power and momentum of the biotech industry, the author says the tide may now be turning. Americans, Heinberg says, are waking up to the dangers of genetic engineering. In part, that’s owing to new scientific evidence about the unexpected side effects of the technology, including a recent Cornell University study that found that pollen from a widely planted variety of genetically modified corn kills the larvae of the monarch butterfly, an important pollinator.

Still, despite growing public awareness, Heinberg–who is a faculty member at New College of California–argues that the urgency of the situation demands such radical actions as crop pulls–and such radical critiques as the one made in his book.

“This process [of implementing biotechnology] is moving very quickly, and I’m convinced that the likelihood of serious unintended consequences is very large,” Heinberg says. “I think in a situation like that, somebody does need to yell fire in a crowded theater, because there really is a fire.”

MANY AMERICANS don’t realize how deeply biotechnology already touches their lives. The United States now grows an estimated 75 million acres of genetically modified crops. Roughly 60 percent of the processed foods sold in America contain genetically engineered ingredients. But the average consumer doesn’t know that, in part because no labeling is required for such food–a fact that looms large in Heinberg’s book, which calls for legislation mandating the clear labeling of altered ingredients.

Of course, such measures have been proposed before, but so far both government regulators and the biotech industry have strenuously resisted. That’s partly because many polls show that a large percentage of Americans would refuse to consume food they knew to be genetically engineered, so putting such a label on a product could bankrupt a company.

Some defenders of biotech also argue that there’s no good reason for labeling because genetic engineering is, in one sense, nothing new. After all, humans have been breeding plants and animals to get desirable characteristics for thousands of years.

Genetic engineering, some supporters say, is simply a high-tech version of that traditional process.

But Heinberg and many others argue that such modern techniques as cloning and gene splicing allow scientists to tinker with organisms in fundamentally new ways to produce, as Heinberg puts it in Cloning the Buddha, “genetic changes that would never occur in the wild or through the most intensive breeding.”

The results of that process can be both impressive and terrifying. On the one hand, scientists are producing crops that grow quickly and resist pests. On the other, genetic engineering sometimes produces unexpected side effects that range from the inconvenient–like food allergies–to the potentially catastrophic.

In his book, Heinberg tells the alarming story of an attempt in the early 1990s to genetically redesign Klebsiella planticola, a common soil bacteria, to break down lumber companies’ wood waste into useful fertilizer.

The new organism was apparently on the fast track to EPA approval before an alert Oregon microbiologist determined that it was both lethal to plants and extremely competitive. If it had been introduced into the general environment, the new strain of Klebsiella might have spread quickly and wreaked ecological devastation, turning forests and fields into dead sludge.

HEINBERG USES such incidents to buttress his contention that Americans must work quickly to learn everything they can about genetic engineering in order to come to grips with the urgent practical and moral issues that surround it.

“This technology is poised to reshape our lives at very basic levels: the food we eat, how we reproduce, what our children look like,” Heinberg says. “These are pretty important issues, and we really can’t just leave them to the experts, because the experts tend to be very highly trained in very narrow fields of knowledge. They really aren’t equipped to make the kind of basic ethical judgments that affect all of society.”

Cloning the Buddha goes straight to what its author sees as the root of the problem–the mechanistic scientific worldview that spawned biotech in the first place. In an era where new technology presents us with difficult choices, Heinberg believes that we need a new ethic–and even a new spirituality–to sort out right from wrong.

For an example of these sticky dilemmas, Heinberg turns away from agriculture to offer his readers the difficult issue of genetic therapy, which may soon be used to alter the DNA of human gametes or fertilized eggs to prevent some diseases.

“Well, on a micro level, yes of course, anybody would have to agree with that,” Heinberg says. “But how do you define a disease? Tay-Sachs? Sickle cell anemia? Sure, everybody would agree that those are diseases. How about shortness? Or male-pattern baldness? Are these diseases that would require genetic intervention?

“Where do you stop?”

At a time when, according to Heinberg, a basic genetic engineering laboratory can be put together for as little as $20,000, gene therapy is just one of the difficult issues likely to confront Americans in the near future.

The author hopes we’ll be ready.

“It’s entirely possible that genetic engineering could have a wide range of ethically acceptable uses once we have put it under some kind of public control and scrutiny,” Heinberg says. “What I’m saying is that we haven’t had that conversation yet. We haven’t thought through the issues.”

A three-part series on biotechnology begins at New College of California on Thursday, Aug. 26, with Heinberg’s reading. The series continues on Sept. 28, with a lecture by Dr. Ignacio Chapela, chair of the Microbial Biology Department at UC Berkeley. Finally, on Oct. 26, Britt Bailey, co-author of Against the Grain: The Dangers of Genetic Engineering of Crops, lectures. All events begin at 7:30 p.m. at 99 Sixth St., Santa Rosa. A $5 donation is requested. For details, call 568-0112.

From the August 19-26, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.