Like Whites on Race

The race struggle shifts to white studies. Now what?

By Jeff Howe

WHEN IT COMES to the humanities, academic disciplines have more in common with sitcom legal beagle Ally McBeal than might be immediately apparent. This is not to make light of higher education; great works of art, great scientific discoveries, and great tweedy fall looks have all emerged from our prestigious university system. But like the show that made bi-gendered bathrooms a topic of national conversation, disciplines emerge from our culture and are a vehicle for observations about that culture.

Both offer snapshots of contemporary American society.

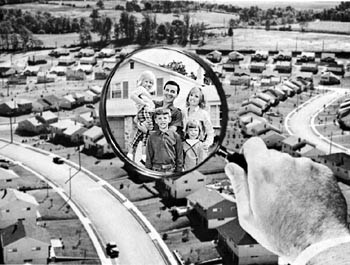

From this perspective, critical white studies–which, if not a discipline in their own right, do constitute an academic Zeitgeist of sorts–begin to make more sense. The premise of white studies is fairly simple: White is a race like any other; the close examination of white culture will produce knowledge and understanding–a consciousness–that will contribute to the dismantling of those subtle, pervasive privileges that whites enjoy at the expense of other races.

“The question becomes, Can you talk about the contributions whites have made without discussing the terror that whites inflicted on other races?” says Charles Gallagher, a sociology professor at Georgia State University who has taught classes on race and ethnic relations both there and at Colorado College, in Colorado Springs.

The influences that shape this movement seem, at first, contradictory. White studies may be the first strategy of social inquiry to embody both the success and the failure of multiculturalism on college campuses. In this way, the discipline of critical white studies is very much of our confused world, a world in which Ally McBeal represents either feminism’s wholesale retreat or its final victory, depending on who’s providing the analysis. It’s a world in which Politically Incorrect draws millions of weekly viewers, while politicians scrutinize their speeches for language that might offend anyone.

The ideas underpinning the study of whiteness seem evident: After years of failed policies and dashed hopes, Americans are willing to have a go at just about anything that proposes to suture our gaping racial rifts. So it’s surprising that until the University of California-Berkeley hosted a conference addressing whiteness studies in the spring of 1997, the field hadn’t even appeared on the national radar screen. It’s true that the tradition of ethnicity scholars studying white culture dates back to such classic essays as W.E.B. DuBois’ “The Souls of White Folk,” from 1920. But it’s because the history of America’s race struggles involved consolidation (e.g., bloc voting) and strategic exclusion (e.g., black nationalism) that white people who studied ethnicity tended to ignore their own.

Until now, that is. As with any trend, the impetus behind critical white studies bubbled up simultaneously from several different quarters and has taken many different forms. Matt Wray, a professor at Berkeley and co-editor of White Trash (an anthology of essays exploring topics such as slasher movies and the cult of Elvis), studies chain-saw art. Noel Ignatiev, a fellow at Harvard and editor of the Race Traitor journal, proposes to study whiteness only as a method of abolishing whiteness altogether. Jeff Hitchcock is more of a pragmatist; he founded the Center for the Study of White American Culture and holds conferences intended to “improve people’s ability to function in multicultural society.”

WHITE STUDIES draw together a diverse group of people with a diverse set of objectives, and thus can’t be pegged to a traditional ideological spectrum. What most tend to agree on is that traditional liberalism has become bankrupt, and that the path to racial equality involves “racializing” whiteness.

But the emergence of white studies has raised the ire of critics from both the right and the left. Shelby Steele, a race scholar at Stanford University and winner of the 1991 National Book Critics Circle Award for The Content of Our Character, feels white studies reaffirm notions of “black despair” and “white privilege,” and claims whites will use it to absolve themselves of racism. Other race scholars have expressed concern that white-studies departments will compete with other race and ethnic studies departments for already-scarce funding and resources.

Even white-studies scholars themselves caution against interpreting the examination of white culture as the celebration of white culture. Most ominous of all concerns is that white supremacists could co-opt white studies for their own purposes. It sounds ridiculous, but white supremacists share many of the same interests, if none of the same ends, as white-studies scholars.

“I’ve been in high schools where kids say, ‘Hey, if they get a Latino club, we want a European club.’ And these are the kids who are going to be showing up at colleges offering courses in white studies,” says Chip Berlet, a senior research analyst at Political Research Associates, a Boston-based think tank that tracks far-right groups. Berlet has spent the past 17 years talking to white supremacists and advises white-studies scholars to begin taking these movements seriously. “Pat Buchanan is on TV every night in this country, talking about issues that are often white ethnocentric. Critical-white-studies people simply don’t have that exposure. There are people who are going to take the themes of a critical-white-studies course and twist them into supporting white supremacy.”

Gallagher has interviewed dozens of college students about perceptions of their own color. He readily acknowledges the threat posed by white-pride movements, but says the hope is that after taking a class examining their race, students leave with a heightened sensitivity to what it means not to be white. “A lot of white 18- to 20-year-olds are struggling with their history, with a narrative of whiteness that doesn’t evoke terror, slavery, or the Ku Klux Klan,” Gallagher says.

“But in constructing a positive identity, they also have to talk about how whites have always been privileged.”

Because each successive generation of white Americans moves further and further away from its country of origin, a vacuum has opened up, and many students, Gallagher says, are simply trying to find an ethnic identity. The goal is to expand that search to include an understanding of how other ethnicities have shaped American culture as well.

When Gallagher taught at Colorado College, one of his white students was so impressed by his class that she focused her senior thesis on how fellow students perceived their racial identity. “I thought of myself as a white person,” says Jennie Randall, who is now a first-year law student at the University of Pennsylvania. Gallagher’s class, Randall says, “made me realize there were a lot of assumptions I took for granted.” Randall, who grew up in predominantly upper-middle-class environments, says her exposure to non-white students had been negligible.

“For me, the issue of race had always been somewhat troubling, and I think a lot of white people have a lot more anxiety about race than they’re willing to admit,” she says. “Because there’s an assumption that race is only an issue for blacks, it’s surprising to discover that you’re as affected by it as anyone of color.”

Randall adds that of the white students she interviewed for her thesis, only those who had taken classes concerning racial identities had thought about their own whiteness.

For students like Randall, who would be unlikely to join the Klan even without a class in white identity, the process of examining herself as a “racialized other” has enriched, but probably not changed, her life.

For a student teetering on the edge of white pride and white consciousness, however, a curriculum in white studies could turn anger and confusion into understanding and empathy.

It’s a tall order to fill–to turn the tide of white resentment and prepare America for a harmonious, equitable coexistence in an increasingly multiracial society–a society in which the melting pot looks more like gumbo than New England clam chowder.

From the February 18-24, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.