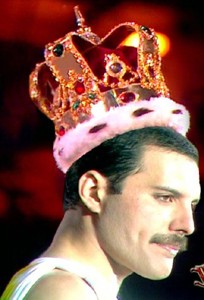

King of Queen: Freddie and the lads didn’t score a classic with the faux whimsy of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody.’

Sound Salvation

Defining the classics in classic rock

By Karl Byrn

I love classic rock. Sonoma County’s KRVR 97.7-FM (whose motto is “Classic rock for the North Bay”) is the first and favorite preset on my car radio dial. I attended high school in the ’70s, and I enjoy the familiar music of their commercial-free 10-song sets during my commute time. But I’m also a channel changer–I’ll cruise for new rock on KXFX, hip-hop on KMEL or whatever country, oldies and roots music is coming in clearly.

I can’t love KRVR itself, though, because its definition of classic rock is based on age and era. One of the station’s DJs recently made an amusing comment as to whether “we” the listeners now thought the same about the names of new bands like the White Stripes and Hoobastank as our parents did of “our” bands and band names like Mott the Hoople. I wondered what the difference is. Anyone aware of Mott and ’70s glam rock can’t think Jack White and nu-metal are that weird.

But the classic-rock format has been conceived as a marketing category based on this separation of new and old rock–Eric Clapton and the Eagles over here, Green Day and Nirvana over there. In this context, classic rock is merely the new oldies–feel-good, easy-going hits for the second wave of baby boomers.

But isn’t there more? Isn’t truly classic rock music an artistic force that transcends the nostalgia of a single generation? Webster’s Dictionary says a classic is foremost “of recognized value; serving as a standard of excellence.” What, then, makes rock music of any era truly classic?

The so-called test of time can be deceptive. Witness the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s failure to induct immeasurably influential ’70s acts Black Sabbath and the Sex Pistols, not to mention such a mainstream classic-rock poster act as Lynyrd Skynyrd. The greatness of any piece of rock music simply can’t be judged by its generational acceptance.

More accurately, the “standard of excellence” has little to do with era-based comfort and lots to do with the core values of rock ‘n’ roll. Rock’s core values have historically included idealism, self-determination, lust for thrills, dismissal of authority, restless energy, brutal self-evaluation, confessionalism and a quest for community. Rock isn’t classic because the band played it at your 1978 prom; rock is great when its “recognized value” makes you dig deeper.

My brother and I recently debated the merits of Queen’s mammoth classic-rock hit “Bohemian Rhapsody,” a song he admires and that I disregard. This was partly a matter of taste: he likes baroque rock; I like bar-band rock. He tried defending the song as a portrait of teenage angst, but I busted him on the error of defining classics through a lens of age-based acceptance. “Bohemian Rhapsody” is not a genuine expression of teen angst; it is, rather, faux play-acting, whimsy for whimsy’s sake. As art, it isn’t born of a desire to release and resolve turmoil; it’s born of a desire to be clever.

He finally offered that the real thing, the genuine rock article, is more convincingly conveyed on a ’90s classic, Nirvana’s mammoth “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” That’s right, I’m saying that “Bohemian Rhapsody” has a lesser claim to classic-rock status than “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” since it reveals less of rock’s core values. FM rock hits of the ’70s are good marketing tools, but profound classic rock keeps a clearer essence of rock ‘n’ roll alive.

A narrow, generation-based focus misses not just classic-rock values, but essential rock music as well. Consider the impact of two great songs now limited to “oldies” status. On Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue,” the 16th notes that cascade over the tom-toms predict heavy rock’s double-bass drum sound, and on Elvis’ “Hound Dog,” the rhythm chord that scrapes through the verses is slightly out of tune and distorted, predicting everything from the Who to Sonic Youth.

Classic-caliber rock can be found in any era. If the classic-rock format could ditch its need for age-based marketing, a commercial-free 10-song set could sound as richly compelling as “Shapes of Things” (the Yardbirds); “Unsatisfied” (the Replacements); “Catharsis” (Anthrax); “Stand!” (Sly and the Family Stone); “Daughter” (Pearl Jam); “In Between Days” (the Cure); “Kentucky Rain” (Elvis Presley); “Nobody’s Crying” (Patty Griffin); “White Man in Hammersmith Palais” (the Clash); and “You Never Can Tell” (Chuck Berry).

That’s what I want from classic rock–not a marketing category that’s built to make for better business by comforting me, but rather a “standard of excellence” that’s built to make for better listening and living by challenging us.

From the April 13-19, 2005 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.