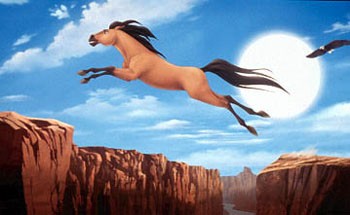

How The West Was Won: The stallion of the Cimarron gets subversive.

Free ‘Spirit’

Has Dreamworks delivered the year’s most subversive kiddie-flick?

Writer David Templeton takes interesting people to interesting movies in his ongoing quest for the ultimate postfilm conversation. This is not a review; rather, it’s a freewheeling, tangential discussion of life, alternative ideas, and popular culture.

Stephanie Mills is a connoisseur of what she calls “the subversive moment.” She nurtures, observes, collects, and records such moments the way some people hunt for weird mushrooms. Her numerous books (In Service of the Wild, Turning Away from Technology, In Praise of Nature), while standing as radical manifestos against the rampant over-consumption of natural resources, can also be viewed as important historical compilations–little snapshots, if you will–of the modern age’s most subversive moments, actions, and ideas. Among those is the widely reported, now legendary moment in 1969 when a young Stephanie Mills gave an attention-grabbing commencement speech at Mills College in California, denouncing the overpopulation of the planet and vowing to remain childless for the rest of her life.

So, to put it mildly, Stephanie Mills knows subversion when she sees it.

Even when it shows up in a G-rated movie with animated horses.

“This movie is a cinematic questioning of the very idea of conquest,” says Mills, taking a seat in a bustling coffeehouse, mere moments after catching Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron. A product of Dreamworks Pictures–whose last animated effort, Shrek, boasted big, steaming pile of subversive moments–Spirit harnesses the breathtaking beauty of traditional animation in its tale of a wild Mustang stallion in the mid 1800s fighting to remain unbroken and free after capture by U.S. Cavalry soldiers.

“It’s a very subversive story, actually,” says Mills, “because it’s a very subversive act in this culture to question the conquest of the West. There was a lot that was challenging about this movie. At its core, I thought, the film is a captivity narrative. It made me think of the subjugation of African Americans. It’s really a slave-revolt story, in some respects, and a tale of the domestication of wild animals and a study of the compatibility of wildness and empire.”

“That’s an awfully big load for a movie–especially a kids’ movie—to have to haul around,” I remark.

“Maybe,” she replies. “And it may not have been done perfectly here, but it’s obviously time to ask those questions again–and why not do it in a children’s movie?”

In her new book, Epicurean Simplicity, Mills takes subversion to a meditative level in a funny and mesmerizing memoir, a poetic chronicle of Mills’ own recent efforts to embrace, in daily practice, the simple-pleasure philosophies of third-century teacher Epicurus, who advocated a life of good food, good art, good friends, good conversation–and nothing more.

Fortunately, movies fall into the category of good art. And as Spirit proves, good art can often set the stage for challenging revelations. As Mills sees it, the cavalry soldiers in Spirit more or less represent the forceful domination of the West, but it is the railroad–specifically one enormous steam engine, hauled Fitzcaraldo-style over the plains by a team of straining horses–that is Spirit’s most powerful metaphor, a symbol of the high-speed onset of technological expansion.

“The story of the American railroad and the story of the conquest of the plains are really chapters in the great textbook of how economic growth was fostered and expanded,” she interprets. “Since indigenous people–since the wild itself–stood in the path of empire, it all needed to be done away with or ghettoized or domesticated. And it doesn’t look as if their domestication has been all that successful.

“The horse,” she adds, “was a great symbol of that conflict.”

“So, isn’t it kind of ironic,” I ask, “that an antitechnology message is being conveyed in a movie that, according to its makers, is the most technologically advanced animated film in history?”

Mills nods, thinking it over before proposing, “Earth is an ecological planet. No matter how brilliantly we can manipulate technology, it seems unlikely that we’ll ever be able to cut the umbilical cord from Mother Nature. As a species, we are tied to the planet.

“That said,” she smiles, “in this case, I think they wielded the technology well.”

From the June 13-19, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.