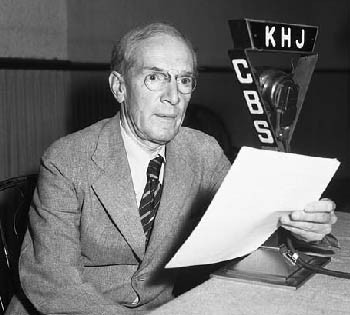

Muckraker: Novelist, journalist, activist and politician Upton Sinclair inhabited for 50 years a California that we still closely know today.

King of California

Half a century of Upton Sinclair’s state of the state

By Kathleen Henry

Hugely energetic, an avowed socialist who was nonetheless patrician in manner, a California gubernatorial candidate now largely dismissed from the modern imagination, novelist and essayist Upton Sinclair lived a life that can barely be contained in one book. Teddy Roosevelt coined the term “muckraker” to describe Sinclair upon the publication of The Jungle, the author’s brutal exposé of the Chicago meatpacking industry. Arthur Conan Doyle called him one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century, the “Zola of America.” Albert Einstein came to visit him at his Pasadena home, Irving Thalberg turned one of his novels into an MGM movie and he won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1943. He wrote 92 books and died in 1968 at the age of 90.

A lifelong activist, Sinclair lived in California for 50 years, between 1915 and 1965, where he wrote about everything from the state’s suppression of his political ideology to fad diets. A new mini-anthology of Sinclair’s California works, The Land of Orange Groves and Jails: Upton Sinclair’s California (Heydey; $16.95), provides a fascinating glimpse into that era of the golden state, whose public debates from the past still resonate and bear an eerie resemblance to those of today.

Orange Groves editor Lauren Coodley, a professor of California history at Napa Valley College and a Sinclair scholar, has chosen colorful excerpts from his novels, essays and pamphlets, prefacing each with insightful and impassioned commentary sympathetic to Sinclair’s ideals, writing that “his holistic vision, quintessentially Californian, flourished in a land whose own essence ranged so eclectically from orange groves to jails.”

The book is a must-read for students of literature, history and political science, for Sinclair bridges all three disciplines. Those reading him for the first time will be struck by the unrelenting freight train of his take-no-prisoners style. He is didactic, but unabashedly so, and his works are polemical page-turners.

Coodley observes that Sinclair has never been as relevant as he is now, and an inventory of his writing confirms that he wrote broadly on free speech, food safety, diet and health, the oil and film industries, political corruption, the preservation of nature, women’s rights (he favored equal division of child care and housework), all while relentlessly chronicling the tyranny of low wages, the decline of organized labor, the plight of the unemployed, the stranglehold of big business over government, and the failure of education. Sound familiar?

When five Russian immigrant teachers were arrested, tried and jailed for daring to open a socialist summer camp for children, flying the red flag of the Soviet Union in remote and tiny Yucaipa, an outraged Sinclair wrote an essay in The Open Forum magazine that typifies his style of sarcastic invective: “Friends and comrades . . . who will read these words will join me in acclaiming the courage and loyalty . . . of patriots who saved the orange country from the peril of five Russian Jewish working-girls and a little piece of red silk, home cut and home sewed by the fingers of working-class children. . . . [N]othing, I am sure, can claim a higher place in history’s roll than the raid upon the Yucaipa camp.”

Sinclair was not afraid to protest and go to jail for his beliefs, calling it an “adventure.” He even describes a secondary gain from incarceration: weight loss.But Sinclair was not without contradictions. His favorite sport was the then-patrician game of tennis, and he played it with Henry Ford. He lived in Beverly Hills for 10 years and hobnobbed at Hearst Castle. A friend described him at the age of 45 as “a slight, wiry, graying figure, an excellent tennis player, an eager talker, wearing the cast-off clothes of a rich young friend . . . boyish, impulsive, trustful, stubborn, fondly regarded as impractical by those who love him.”

He was, however, practical enough in 1931 to negotiate a $25,000 fee from MGM, a fortune at the time, to make his novel Wet Parade into a film starring matinee idol Robert Taylor. By the early 1930s, Sinclair was one of the bestselling authors in Europe and Asia. His Lanny Budd series of novels sold over 1 million copies in the United States and was translated into 20 languages.

Sinclair made a run for governor of California in 1934, which he lost by some 25,000 votes, a narrow margin considering that the state’s newspapers and industrial giants railed against him, the Los Angeles Times denouncing his supporters as a “maggot-like hoard.” His platform proposed the centralization of agriculture modeled on the communes of the Soviet Union, and it was reported that a woman took poison upon hearing he lost the election.

Noting that Sinclair had come to live in California for his health, Coodley includes a prescient and hilarious tract on diets, published in 1924, where he describes his serial adoption of vegetarianism, fasting, conversion back to meat, eating sand, consumption of starch and raw foods, and finally “natural” foods. His ultimate conclusion has the ring of today’s bestselling diet books: “Get yourself a simple and rational diet, consisting of the natural and wholesome foods . . . and a reasonable amount of sleep, and then learn as quickly as possible to forget your diet and interest yourself in something worthwhile in life outside yourself. That is the great secret of health, both of mind and body, as well as of all happiness and true success in life.”

Coodley gives just enough of a glimpse into Sinclair’s background to put perspective on his writings (although the biography junkies among us would have liked more) and spikes her text with enlivening details, even tracking down Tyrone Power’s secretary and corresponding with her about MGM optioning the Lenny Budd novels as a vehicle for Power.

The grandchild of wealthy Southerners, Sinclair grew up in poverty in New York and wrote hauntingly of his father’s alcoholism: “I would walk for hours, peering into scores of places, and at last I would find him, sunk into a chair or sleeping with his arms on a beer-soaked table.”

He crusaded against alcohol for the rest of his life, and like all children of alcoholics, he was extremely observant and brought this power to evocative descriptions of the human condition. In the short story “Golden Scenario,” unpublished until 1994, he writes: “She was a woman of forty or so, brunette, with the memory of beauty upon her; but now she was thin and haggard, with dark shadows under her eyes. She was evidently laboring under strain, and there was a suggestion of wildness about her.”

Sinclair entered New York City College at 14, and by 17 was at Columbia University, where he kept two secretaries busy taking dictation for dime novels he wrote to support himself and his parents.

He married three times, had a son, traveled throughout Europe and founded a socialist commune in New Jersey in 1906. His works are so numerous and varied that one gets the impression that not a single event in his life escaped his pen. And while his prose can be too florid, his descriptions too unrelenting, his themes too one-note, his work is also gripping, compelling and admirable, and still remarkably relevant in 21st-century California.

From the February 16-22, 2005 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.